History

The story of Jamaica Bobsleigh and Skeleton

Crashing Start

Two American businessmen, George Fitch, the first President and William Maloney, who at the time both lived in Jamaica, formed the JBF. These opportunistic and enterprising young men latched on to a novel idea one night in Kingston. Having seen the local pushcart derby and noted its similarity with bobsledding, and recognizing the abundance of athletic talent in Jamaica, both gentlemen concluded what was not so obvious, that Jamaica and bobsledding was a natural fit. Supported by Mr. Michael Fennel, President of the Jamaica Olympic Association, the two gentlemen proceeded to but in place the elements of a dream that was destined to become a legend.

The first challenge was to recruit athletes for the program. Despite the appeal of the opportunity to compete in the Olympic games, this challenge proved formidable.

Read More

At the first recruitment meeting, the story goes that George Fitch gave an introductory talk on the sport to a hall full of curious and hopeful young athletes. He then proceeded to turn off the lights to show a video clip on the sport, which had a few crashes, some of them quite frightening. When the lights came back on, George found himself standing in an almost empty hall. Desire turned to dread and men fled. The organizer’s determination to go on despite this early setback was to come to characterize Jamaica Bobsleigh. Running out of options, the founders approached the Jamaica Defence Force to ask for volunteers, or to have prospects ‘volunteered’ as only the army could do. Out of this came the first stalwarts of the Jamaica Bobsleigh team, Dudley Stokes, Devon Harris, and Michael White. Through various other selection activities other athletes were added, Freddie Powell and Clayton Solomon. This initial athlete selection was completed by October 1987. Caswell Allen was to join the team later.

Funded by George Fitch and the Jamaica Tourist Board, the athletes embarked on a ‘crash’ course in bobsledding. The comfort of running and weight training in Jamaica was soon destroyed with the harsh realities of bobsled training in Lake Placid, New York, and Igls, Austria. Dudley Stokes by this time had been selected as the driver for the team based on his exceptional concentration and helicopter piloting experience. Learning was difficult and painful. The team only had access to poor equipment and crashed repeatedly. Coaches were retained from America and gave an immediate boost to the team. Things improved even more with the capable assistance of Sepp Haidacher of Austria who became and remains the team’s godfather.

By this time the team began to receive attention from the North American media. The angle was predictable – Jamaica Bobsleigh – what a laugh. This attitude of the media did little to help the team in its struggle to be recognized by the Fédération International de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing (FIBT). Where, in true Jamaican style, the team expected a warm greeting and welcome from the FIBT, instead it found a cold shoulder and stony faces. Determined, the JBF succeeded in entering both a 2-man and 4-man team in the XVth Olympic Winter Games that was held in Calgary, Canada in 1988.

By the start of the 1988 Winter Olympic Games the popularity of the team was widespread based on grassroots support from those who favoured the unusual and the underdog. Supporters around the world formed the team into their own conceptions, a popular one being that the team was made up of dread-locked, fearless, semi-athletes out to conquer Babylon. The team in the mean time was caught off guard by its popularity. A funding raising party held during the first week of the Olympics was hugely popular and T-shirts and sweatshirts were now being sold by the box-load, and the team’s song ‘Hobbin and a Bobbin’ was to be heard everywhere. The task of public relations and sales fell to Freddie Powell who adopted this role naturally. He was soft-spoken, kind, bearded and was a reggae singer, ideal for public consumption.

While the public hysteria over the team mushroomed, the matter of the Olympic competition remained fixed in the minds of the athletes. First on the schedule was the 2-man competition. Driver Dudley Stokes and brakeman Michael White were entered for that competition. At the end of the four runs, the team placed 35th.

Relieved by actually doing, at least in part, what the team set out to do, the mood in the camp relaxed and focus easily shifted to the 4-man event. As history would have it, the US Olympic Hockey team was eliminated earlier than the US media would have liked which left them with airtime and nothing for consumption by the US viewing public. They needed something exciting, different, not threatening and entertaining. Jamaica Bobsleigh fit the bill. With the full attention of the American media, the popularity of the team was now at its zenith. Team members abandoned all plans for walking around outside the Olympic village for fear of being mobbed. Requests for appearances, mail, phone calls all became unmanageable. We were in the midst of a phenomenon that the best public relations agencies could not create, and that we could not control. Still, the focus of the athletes remained intense.

Early in the training for the 4-man event, an injury was sustained by one of the pushers. This development was a cause for great concern, as the coaching staff believed that the team stood a good chance of posting a respectable finish in this event. With a weakened team, the opportunity to prove the sceptics wrong was threatened. Faced with this scenario, team captain Dudley Stokes made the bold suggestion that his brother, Chris Stokes be recruited onto the team. Chris was a Jamaican high school sprint champion who had a noteworthy collegiate athletic career at the Bronx Community College and the University of Idaho and was then in training for the 1988 summer Olympic Games selections in Jamaica. The fact that Chris was not at the Olympic Games and had never been in or seen a bobsleigh would normally be factors which would eliminate one from consideration for competitive duties but the coaching team agreed to give it a try. Upon arrival, Chris immediately made a difference to the teams start times. Combined with the power of Devon Harris and the smooth speed of Michael White, the team was once again in a position to compete with the best.

Things went wrong....

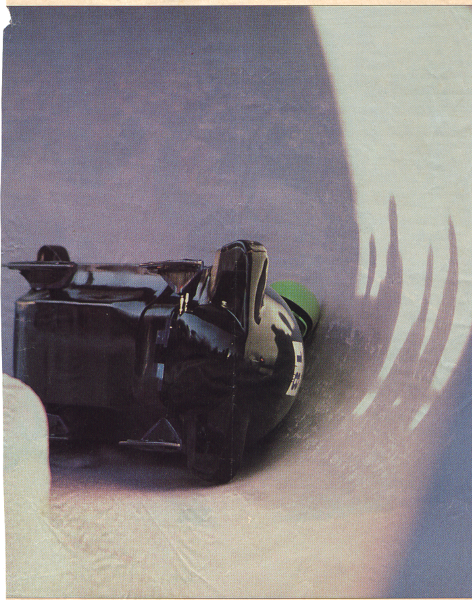

Things went wrong from the beginning in the 4-man event. On the first run, the push bar of the worn sled collapsed while driver Dudley Stokes was at full speed running downhill. The fact that he made it into the sled was an athletic feat unto itself. On the second run, Michael White had trouble sitting in the sled and was in an almost erect posture well into the first turn of the run. The first day of competition ended with the first two runs. We had gone to the top; we had made it to the bottom. The fans were happy and the media had their fun. Yet, we spent the night reflecting on how we could improve for the next day. There was no more time for theory. All that mattered now was to do what we knew how to, to execute under pressure. The second day of competition was bright and sunny; the team arrived at the track focused and energetic. Again, the fragile optimism was soon dashed. Driver Dudley Stokes fell on his walk up the track and immobilised his left shoulder, determined to go on he applied some cold-spray to ease the pain and walked to the starting line only to be told that the national team coach had that morning left the Games. In front of millions of people, the team was at that moment at its loneliest. With only seconds to focus the team came together and with a collective energy committed itself to go forward, to finish the job. In an inspired moment the team started off the hill in the seventh fasted time for all competitors. Achieving speeds previously un-reached, Dudley Stokes lost control of the sled coming out of the Kreisel, a huge 365-degree turn on the track and at approximately 85 miles per hour the sled crashed, pinning the drivers head against the inside wall and creating an echo that was heard around the world.

So close to doing what could not be done, the team did what the cynics expected. Crashed at the big show. The FIBT establishment was vindicated; they said that Jamaica was not prepared for the Olympics and the team proved them right. The media cast the team as jokers and ‘Sunday Sledders’. It was fun while it lasted. The time had come for our sideshow to make room for the real sledders.

The founders, who had realised their prospective short-term goals, envisioned no future for the sport. Maloney obtained his Olympic experience by becoming a member of the Jamaican delegation and Fitch developed a thriving merchandising business and would subsequently have a movie, Disney’s ‘Cool Runnings’ made of the endeavour. The end of Jamaica Bobsleigh was in sight; the fifteen minutes were up.

The Wilderness Years

Confronted with facts, figures, and arguments all pointing in the direction of quitting, the team took it up on themselves to continue competing. Team members saw themselves as athletes, not as showmen. It was this spirit that was to see the team through the wilderness years, from 1988 – 1993. George Fitch was persuaded to stay on during a transition period and continued to give invaluable support through the 1992 games. During this period the program was unfocused, and without clear leadership. A flood of athletes entered the program but performance improvements were not forthcoming. An important development was the initiation of the driving career of Devon Harris.

Within three years interest had gradually subsided and by the time the team participated in the 1992 Olympic Winter Games in Albertville, France, it was largely in obscurity. In the 2-man event, the first Jamaican team finished in 35th place while the second Jamaican team finished in 36th place. The four-man team finished 24th.

A TASTE OF THE POSSIBLE

In 1993 the Federation embarked on a serious long- term venture for continued growth and development. Maj. Leo Campbell was appointed president of the JBF and brought his considerable intellect, organizational skills and work ethic to bear on organizing the affairs of the JBF. The single most important decision made during this period was the retention of Sam Bock as national coach. Time was short; the Olympics were less than a year away and much work had to be done. Bock’s focused; no-nonsense, intransigent style fit the times well. There was no time to debate. It was the coaches way or no way. The Olympic effort gained a tremendous boost with the addition of Wayne Thomas and Winston Watt to the roster of athletes. Both were, in short order, to prove themselves among the best pushers in the world.

Read More

The team for the 1994 Winter Olympic Games to be held in Lillehammer, Norway was selected. The athletes were:

- Tal Stokes

- Chris Stokes

- Ricky McIntosh

- Jerome Lewis

- Winston Watt

- Wayne Thomas

- Sam Bock, who worked exclusively with a Canadian team as their private coach, was contracted just six weeks prior to the Olympic games.

In order to maximise the teams potential in such a short period of time, the members were subjected to training 4-8 hours per day in total isolation in the former East Germany at a special push training facility.

The 1994 Olympic Winter Games got off to a dubious start when the 2 man team of Dudley Stokes and Wayne Thomas was disqualified for an overweight sled. A last minute change in equipment led to the combined weight of the sled and crew surpassing the allowable limit by a minute amount, but still overweight.

Years of hard work were soon to payoff. In the four-man event, the Jamaican team surprised everyone with its recently developed world class start, and drove the highly technical track well to finish in 14th place. The team thereby leapt into the elite of the sport, the ‘Top Fifteen’ best Bobsleigh teams in the world. The result placed Jamaica ahead of the Americans, French, Russians and one of the Italian teams.

On the second day of that race, and the final day of the Olympic games, the team shocked everyone by placing 10th in both runs ahead of the 2-man bronze medallist from Italy, former Swiss national champion, Christian Meili and a slew of other powerful teams.

The events at the Lillehammer Olympics proved one of the biggest upsets in Bobsleighing history and arguably in the history of sporting contests between nations. This achievement, coupled with the media hype from the release of the movie ‘Cool Runnings’ served to enhance the image of the athletes worldwide.

The team had dreamt, suffered and overcome. By now, the FIBT, which was under new and forward-thinking leadership, was among the first to congratulate the Jamaican team. The media generally became respectful in its comments though the American media seemed to be searching for ways to sneak out of the corner in which it had painted itself. If we were jokers and we had beaten America, then what was America?

A DREAM DEFERRED

Having come so far against the odds, the only thing that remained a motivator was the quest for an Olympic medal. This goal could now be discussed in realistic terms. Sam Bock remained on as national coach and devised an elaborate development program to bring the team into medal contention by the 1998 Nagano games. Things seemed to progress and then fall behind. By early 1997 team morale was at an all time low and relationships were strained. The dream was quickly slipping from grasp. In that year, Chris Stokes, who was elected President of the JBF in 1995 rejoined the team as an athlete. It soon became clear to all that the situation was untenable and by December of 1997 Bock was no longer national coach. With six weeks to go before the Olympic Games, the team found itself struggling and without a coach. Sepp Haidacher intervened and secured the services of Gerd Leopold, former German national coach, and coach of the Olympic 4-man champion to work with Jamaica through the Nagano Games.

Leopold, brought a degree of unity and commitment to the team which was absent for many years. By the time the team competed in Japan, it had made up for much of what was lost and finished a respectable 21st in the 4-man competition with the same team of Dudley Stokes, Winston Watt, Chris Stokes and Wayne Thomas that competed in 1994.

Devon Harris had returned to the program after a brief absence and worked hard to prepare himself for 2-man competition. His training was assisted by the tremendous support received from the town of Evanston Wyoming under the encouragement of Paul Skog. In difficult circumstances and against the odds Harris performed creditably to post a 29th place finish, the best of any Jamaican 2-man team at that level.

2 man event

Sub Heading

4 man sled grinds to a halt

Sub Heading

Sub Heading

A TIME TO SOW

The 1997–98 season marked the tenth season of Jamaica’s participation in the sport of bobsleigh. During that time, years of struggle and disappointment were rewarded with moments of triumph. Perhaps no single event signalled the triumph of Jamaica Bobsleigh more than Jamaica’s hosting and staging in 1999 of the FIBT’s annual congress, the highest law making body of the sport. The circle had been closed.

Between the end of 1998 and mid 1999, Chris Stokes, Dudley Stokes, and Devon Harris, the last three remaining active athletes from the 1988 team retired from international competition. An era had ended. More than any other, the retirement of Dudley Stokes created a vacuum. For ten years he was the face, the voice, and the inspiration behind the Jamaica Bobsleigh story.

Chris Stokes was re-elected president of the Jamaica Bobsleigh Federation in 1998 and immediately implemented a program to invest in the future of Jamaica Bobsleigh. A new constitution was put in place, which formalized and enhanced the governing guidelines for the sport in Jamaica. A new, highly talented executive was also put in place to guide the program. The advancement of the sport would also require drastic change. This process began with the retention of Trond Knaplund, as national bobsleigh coach.

His first undertaking was to embark on an aggressive recruitment program throughout the length and breadth of the island. This process has led to the selection of an impressive cadre of young athletes who will form the foundation of the program through the 2002 Olympic games and beyond. Their performance to date has been impressive. At the 1999 World Push Championships, Winston Watt and Lascelles Brown placed sixth in the 2-man competition. An ambitious and aggressive program of driver development is now in place.

The Hottest Thing on Ice has taken on the world and has overcome. Now we set our sights on Olympic medals. Having come so far, who would say we can go no further? To quote from the Jimmy Cliff song on the Cool Runnings soundtrack “I can see clearly now the rain is gone, I can see all obstacles in my way, gone are the dark clouds that had me down, it’s going to be a bright, bright sun shiny day”.

WOMEN’S BOBSLEIGH

The possibility of the inclusion of women’s bobsleigh in the 2002 Olympic Winter Games began to be seriously mooted by the FIBT as the 1998 Olympic Winter Games approached. The JBF immediately supported the movement.

Jamaica has had an outstanding record of participation by women in the Summer Olympics including the exploits of Merlene Ottey, Grace Jackson and Deon Hemmings to name a few. The JBF felt that it had the athletes and now the experience in the sport to field a competitive team, and there are many who believe that the opportunity to win a medal in the women’s event is much greater than in the men’s events. Action was taken immediately to develop the women’s program.

The first challenge was to select athletes to go into training. Drawing on its experience, the JBF approached the Jamaica Defence force (JDF), knowing that some pre-selection would have already been done since success in bobsleighing requires a toughness and self-discipline that would have been drilled in the army. Lt. Antonette Gorman, and Capt. Judith Blackwood were the first athletes selected.

Jamaica’s ladies on ice started their bobsleighing careers by successfully participating in a driving school staged in Park City Utah, in October 1998. Following on that, several other outstanding athletes were recruited into the program by coach Knaplund and entered into an intensive training program in Kingston, Jamaica.

Women’s bobsleigh, under the jurisdiction of the Fédération Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing (FIBT), was formally added to the Olympic Winter Games Saturday, October 2, 1999 by the International Olympic Committee.

The women’s bobsleigh competition will join men‘s two-man and four-man bobsleigh for the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City. Men‘s bobsleigh has been part of the Olympic Winter Games since the inaugural competition in 1924.